THE TRADITIONAL ENGLISH PUB AND THE AMERICAN 'INVASION'

While they were ‘over here’ helping with the war effort

during WW2 and bringing Britain victory, thousands of servicemen and

women from the USA, Canada and other Allied countries were stationed

in hundreds of locations across the country.

Rummaging through dusty tomes (and I do rummage) I have over the years

come across a goodly number of references to Allied servicemen

experiencing life in an English pub for the first time – and

then going on to enjoy it again and again. In this article I examine

a handful of servicemen’s views on that most English of

institutions but particularly focusing on the diary of American

serviceman Robert S. Arbib, Jnr.

Rummaging through dusty tomes (and I do rummage) I have over the years

come across a goodly number of references to Allied servicemen

experiencing life in an English pub for the first time – and

then going on to enjoy it again and again. In this article I examine

a handful of servicemen’s views on that most English of

institutions but particularly focusing on the diary of American

serviceman Robert S. Arbib, Jnr.

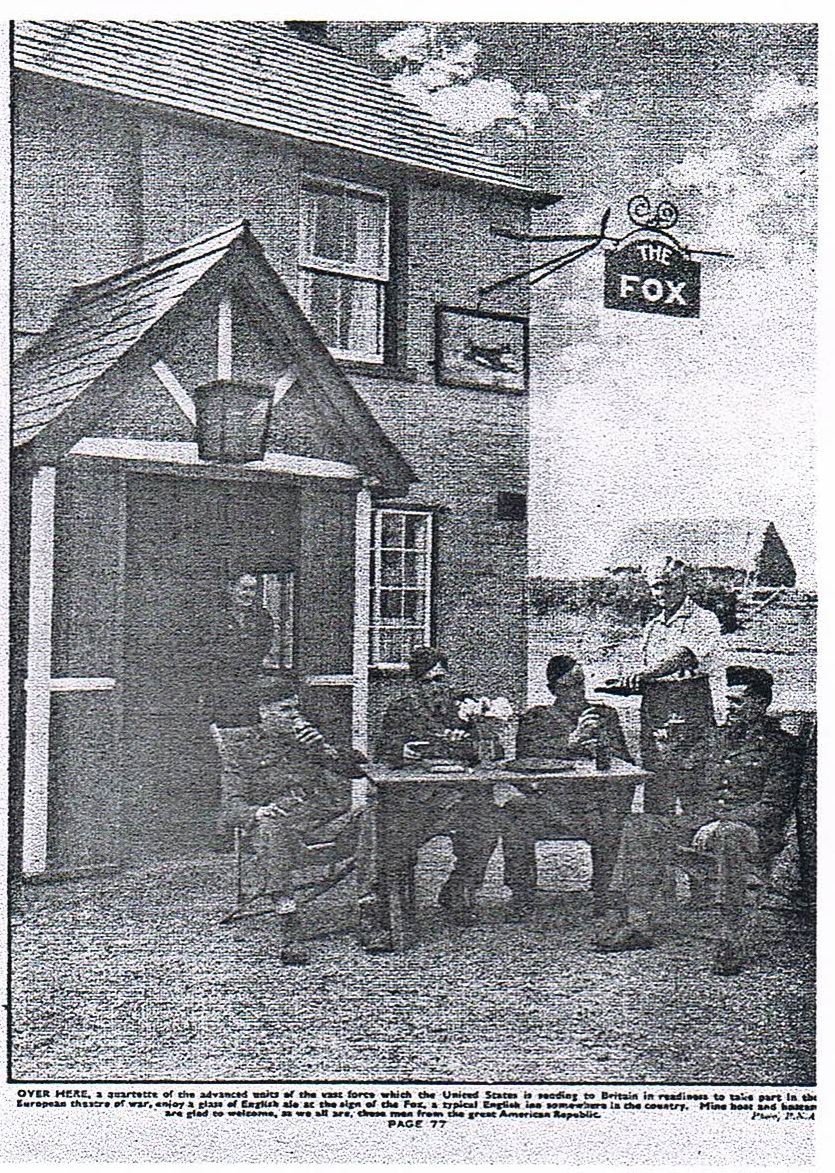

(The image (left) bears the caption ‘OVER HERE – a

quartette of the advanced units of the vast force which the United

States is sending to Britain in readiness to take part in the

European theatre of war, enjoy a glass of English ale, at the sign of

The Fox, a typical English inn somewhere in the country. Mine host

and hostess are glad to welcome, as we all are, these men from the

great American Republic.’)

Arbib was stationed at Debach, Suffolk in 1942. On his third night

there he and six colleagues decided, strictly against regulations, to

wander into the countryside. They wandered as far as the village of

Grundisburgh and there they were ‘officially welcomed to

England’ at The Dog. Arbib described what he and his

colleagues saw as he entered the little pub:

We found three or four small plain rooms with wooden benches and

bare wooden tables. Each room connected somehow with a central bar –

either across the counter or through a tiny window. One of the rooms

had a dart board, and another had an antique upright piano. We went

into the room with the dart board and ordered beer.

News that ‘the Yanks had arrived’ spread quickly and soon

the front room was filled with young men and farm workers in rough

clothes, whilst the back room was occupied by ‘old gaffers, and

their evil-smelling pipes’. The saloon bar filled with family

groups, ‘casuals’, young couples and women. Arbib wrote

of the aftermath of this ‘welcome’, ‘[H]ow

we got home up the pitch-black country lanes to our tents…I

cannot recall.’

[The image of The Dog shown was taken in 2018; reassuring

indeed that this country pub is still serving the community.]

Clearly Arbib soon developed a taste for the English pub. When he was

transferred to Watford, Hertfordshire, Arbib frequented the Unicorn,

a small public house comprising of four rooms which included a Public

Bar that he described as ‘a plain room with plain benches and

tables.’ According to Arbib, Unicorn was ‘typical

of this entirely British institution’, a pub most definitely

for beer drinkers ‘with a dart board thrown in for sport and

conversation’.

In my subsequent research I found no trace of a Unicorn pub

actually in Watford. However, there was (and is) a pub of that name

on Gallows Hill in nearby King’s (sometimes Abbot’s)

Langley.

In my subsequent research I found no trace of a Unicorn pub

actually in Watford. However, there was (and is) a pub of that name

on Gallows Hill in nearby King’s (sometimes Abbot’s)

Langley.

Described on its website as ‘riddled with history’ and a

mere 800 yards from King’s Langley railway station, my guess is

that this is the pub to which Arbib was referring.]

Apparently all in Arbib’s Company agreed that the pub was ‘a

good thing, a great idea, [and] both a social and democratic

institution.’ Indeed, Arbib piled further praise on to the

Unicorn when he wrote

The public house means much to England – as a meeting place,

a poor man’s club, a public forum, a sanctuary and a retreat;

it fills a need for companionship and social life in villages where

there is little other, or in communities where the average home is

not pretentious enough to welcome guests.

[The cartoon (left) featuring ‘Private Breger’, a

character based on a real life serving US soldier, bears the caption

“And they have the swellest omelettes of dehydrated

mushrooms and powered eggs.” As PHS Newsletter Editor

Chris Murray observed, this illustrates the privations of wartime

rationing in England.]

It seemed strange to Arbib that there was so little ‘visiting’

done in England as there was back home in the United States. However,

he appreciated that the village pub partly fulfilled that role by

providing ‘a common living room for all friends’ which

enabled them to meet ‘without any invasion of privacy of the

home.’ Arbib recognised that this was founded upon an entirely

different system of living to that which he and his countrymen were

accustomed to and he realised that to try and reproduce the English

pub anywhere else would surely fail. Indeed, he wrote

…those Americans who dallied with the idea of introducing

the public-house institution to American life soon realized that it

would never work.

As a darts historian, I cannot leave this brief examination of the

‘invasion’ without a reference or two about visiting

servicemen and darts. (Indulge me momentarily please.)

Edie Beed, whose family ran “Ye Olde White Lion”,

Bradninch, near Exeter, for six decades (1918-1978), recalled the

presence of the overseas visitors in the village during World War

Two. The servicemen occupied Nissen huts which had been built all

around the cricket field and found Edie’s pub ‘much to

their liking.’ One evening a customer asked an American soldier

if they played darts or rings (quoits) in his country and the man

replied, “No, we don’t throw nothing at walls.”

C. G. McLean served with the Canadian army in the Second World War

and was stationed in various parts of the UK. During that time he was

always able to find ‘a friendly pub’ where he and his

colleagues were warmly welcomed and where locals were always ‘willing

to show us how to play [darts]’. Indeed, McLean took the

game home with him and in 1997 was still playing in two darts

leagues; one at his local branch of the Canadian Legion and the other

where he lived in a complex in Abbotsford, British Columbia.

Dan Drozdiak of the Royal Canadian Air Force was posted to England in

1943, originally to Bournemouth where he and his friends spent many

happy hours playing darts in pubs.

From Bournemouth Drozdiak was transferred to the Canadian Overseas Postal

Depot at Wembley. Such was his enthusiasm for this ‘new’

game that he declared in a letter to me that he and his friends

‘would sooner play darts then eat’ and formed a

formidable team which went from strength to strength. “We were

very successful”, Dan told me, “We met all pub challenges

and, I don’t wish to brag, but we seldom had to buy a round of

drinks.” When he returned home after the war, darts became very

popular in Legion clubs and in 1997, Drozdiak was still playing darts

in his hometown of Duncan, B.C.

From Bournemouth Drozdiak was transferred to the Canadian Overseas Postal

Depot at Wembley. Such was his enthusiasm for this ‘new’

game that he declared in a letter to me that he and his friends

‘would sooner play darts then eat’ and formed a

formidable team which went from strength to strength. “We were

very successful”, Dan told me, “We met all pub challenges

and, I don’t wish to brag, but we seldom had to buy a round of

drinks.” When he returned home after the war, darts became very

popular in Legion clubs and in 1997, Drozdiak was still playing darts

in his hometown of Duncan, B.C.

[The caption of the contemporary (c. 1944) cartoon, right, reads

“Next time we’ll have to come earlier and see if we

can’t get a better table.”]

Both the institution of the English pub and the pub games played

within them brought much pleasure to those who came over to the UK to

help defend our country in our darkest hours. It is interesting to

note that it has been impossible to truly replicate the traditional

English pub across the ‘Big Pond’ but note too that the

development of the traditional steel-tip game of darts in both

America and Canada has often proved problematical especially with the

emergence in the late 1990s of electronic or soft-tip darts.

Original text © 2008 and 2018 Patrick Chaplin

(This article first appeared in the PHS Newsletter Spring

2008; subsequently updated 2018.)

Sources:

Arbib, Robert S. Jnr. Here We Are Together – The Notebook of

an American Soldier in Britain (London: The Right Book Club,

1947)

Beed, Edie. 70 Years Behind Bars (Bradninch,

Devon: Published by Author, 1984)

Branch-Johnson, William.

Hertfordshire Inns – A Handbook of Old Hertfordshire Inns

and Beerhouses – Part Two – West Herts (Letchworth:

Hertfordshire Countryside, 1963)

Drozdiak, Dan. Letters to Patrick Chaplin dated 9th and

18th September 1997.

East Anglian Daily Times, Wednesday August 15, 2018 (Image of The

Dog)

McLean, C. G. Letter to Patrick Chaplin dated 11th

September 1997.

Pub History Society Newsletter, Summer 2008, page 2.

Cartoon sources and credits:

“And they have the swellest omelettes…” -

Originally sourced by Editor Chris Murray from his own personal

collection, this cartoon appeared in the Summer 2008 issue of the PHS

Newsletter. Introducing Dave Breger’s work Chris M.

wrote

‘Cartoon by Dave Breger (1908-1970) from about 1944.

Private Breger was based on the real life observations of a serving

US soldier who was based in England for part of the Second World War.

Originally showcased in services publications Stars and Stripes

and Yank his cartoons were issued in anthology form in the UK.

Pte Breger was a somewhat naïve but anti authority figure much

loved by the military. This cartoon illustrates the privations of

wartime rationing in England.’

“Next time we’ll have to come earlier…”

- Undated cutting. Exact details unknown but believed to the

work of Sgt. Dick Wingert, c. 1944 and the main character is

‘Hubert’. Wingert drew cartoons for the U.S. Army

newspaper Stars and Stripes.

Website

The Unicorn, King’s (Abbot’s) Langley –

www.unicornpubabbots.co.uk

-

Diary Dates

What we’re doing and when we’re doing it. You might even find a date or two for your diary from other like-minded groups. More details can be found by following the link below.

-

Mail List

Not sure if you want to be a full member yet? Why not sign up for our occasional newsletter, no obligation, no pressure! More details can be found by following the link below.

-

Membership

Becoming a member of the Pub History Society is a great idea. You’ll have access to all of our back issues of our newsletter and even a downloadable bibliography should you need it. More details can be found by following the link below.

The Pub History Society, 16 Bramble Close, Newborough, Peterborough, PE6 7RP ![]()

© Copyright The Pub History Society. All Rights Reserved. | Cookies Policy | Site Map | Contact | Harlequin Web Design | Template by OS Templates